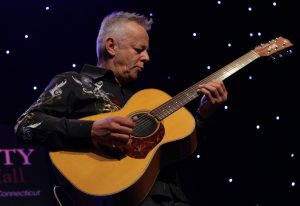

Give a listen to “Old Photographs,” the closing track on Tommy Emmanuel’s It’s Never Too Late, and you’ll hear the distinctive squeak of finger noise as he runs his hands across the frets of his Maton Signature TE guitar. It’s an imperfection in the performance that players typically try to eliminate in practice, and in the hands of a less-secure musician, that sound could easily be edited from the recording with Pro Tools recording technology. But in their own way, those imperfections are perfect. For all of the masterful technique and flashy ability that’s brought Emmanuel recognition among the world’s greatest guitarists, that finger noise lets the audience know he is one of them. That click conveys warmth and humanity. And it demonstrates an honesty in the sound. It’s that integrity that makes It’s Never Too Late a guitar album that’s believable to both studied guitarists and everyday music fans. “It’s all about the feeling of the music,” Emmanuel says. “And it has to make me feel something. I’m still playing for myself, you know, because I figure if I please me, then I’m pretty sure I’m gonna please you. And that’s not an arrogant statement, it’s just quality control.” Quality is laced throughout It’s Never Too Late, the first regular studio album featuring Emmanuel completely solo without guests since 2000. A friend and follower of the late Chet Atkins – who christened Emmanuel a Certified Guitar Player, making him one of only five musicians to receive the C.G.P. distinction from the master – Emmanuel easily skates between musical styles, playing with blues in “One Mint Julep,” infusing Spanish tradition in “El Vaquero” and exploring folk in “The Duke.” An accomplished fingerstyle player, Emmanuel frequently threads three different parts simultaneously into his material, operating as a one-man band who handles the melody, the supporting chords and the bass all at once. That expert layering is evident in It’s Never Too Late on the quixotic “Only Elliott,” the calming title track and the gorgeous “Hellos And Goodbyes.” There’s a science to assembling the parts, and Emmanuel’s technical gift has earned him multiple awards from Guitar Player magazine and made him a Member of the Order of Australia, an honor bestowed by the Queen in his homeland. But the average fan could listen without even considering the precision behind the work, focusing instead on the artful tension and release of Emmanuel’s melodies. That’s how he intends it. “I write as if I’m writing for a singer,” he explains. “I don’t think, ‘Ah, it’s just a solo guitar piece.’ I try to imagine I’m playing with a band or with a singer, but then I play the whole thing as a solo piece and look for ways to give it space.” Emmanuel was destined, perhaps, to become a world-class musician. Given his first guitar at age four, he started working professionally just two years later in a family band, the Emmanuel Quartet. He never learned to read and write music, but he and his brother Phil were dedicated students of the instrument, creating games that helped them identify chords and patterns. They became adept at picking out the nuances of complex chords, a talent that takes most musicians years to develop. Thus, Emmanuel had the music – and the showmanship – and in short order, the music had him. “When I was on stage people lit up,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what it was, but it made me kind of show off and do all the things that cocky little kids do at 6, 7, 8 years old. Music was the worst drug I ever had, and I’m still hooked on it.” Emmanuel pursued it with a passion, continously working in a variety of bands through his school years, including the Midget Safaris (a new name for the Emmanuel kids as they covered surf music) and the Trailblazers, a high-school group that played weddings and parties. After graduation, Emmanuel became one of Australia’s most in-demand rock musicians, playing guitar in a succession of bands, including one of Australia’s best-known acts, Dragon.

He supplemented that with a side job as a studio musician, playing on albums by the likes of Air Supply and Men At Work, and on commercial jingles. It was a rewarding period, but it had its limitations, too. Playing the same set list night after night can turn the road into a chore. And working in a band prevented Emmanuel from making full use of his extraordinary talents and expressing his entire artistic voice. He ventured out on his own and began to treat his shows like a jazz musician would, eschewing set lists, improvising his way through many of his songs to capture and shape the mood of the room. In that process, he was able to latch onto something bigger – a sense of community with the audience and a trust in whatever was in the cosmos that night. “When I play, I feel like I’m plugged into something,” he says. “I don’t know what it is, and I don’t really want to know. I just want to know that it’s there.” He could certainly sense the support. In addition to the standing ovations from his audiences, the recognitions rolled in, including two Grammy nominations, two ARIA Awards from the Australian Recording Industry Association (the Aussie equivalent of the Recording Academy) and repeated honors in the Guitar Player magazine reader’s poll. He’s also been named a Kentucky Colonel, received several honorary degrees and shared a key moment with brother Phil on the world stage, performing during the closing ceremony of the Olympic Games in Sydney. Playing instrumental music that works in any language and travelling nimbly with a small tour group of three – Emmanuel, a sound engineer and a merchandiser – he was able to build a global audience that encompasses not only Australia, but the U.S., the United Kingdom, Europe and Asia. And he earned the opportunity to work with the likes of Eric Clapton, Doc Watson, John Denver and the incomparable Atkins. Emmanuel teamed with Chet on a 1997 project, The Day Finger Pickers Took Over the World, which proved to be Atkins’ final project. Atkins practically handpicked Emmanuel as his creative heir, though he never intended for Tommy to be a simple clone. “The things he respected about me were the things that I respected in myself, which is I stole as much as I possibly could from him, but then I made everything my own,” Emmanuel says. “I totally went in my own direction, and he really admired that about me. I told him, ‘I can’t be you, and I don’t want to be you. I’m me, and I’m gonna get on and do what I do.’ And he said, ‘That’s right.’ He said, ‘There’s enough people out there doing the worst job of trying to play like me.’” The “me” that Emmanuel has established is one with a can-do spirit. The message behind his work is optimism, and that’s a clear part of the ethos in It’s Never Too Late, a title inspired by the birth of a daughter, Rachel, just months before he turned 60. “When you have a child at my age, boy, do you have a reason to get going,” he says with a laugh. “You have a lot to live for.” He channeled that inspiration into the album, half of it recorded in a spurt of energy in Nashville, his current home.

When he did a benefit in Los Angeles, Emmanuel found extra time to work with recording engineer Marc DeSisto on the remaining tracks, and the atmosphere was so great that he revisited several of the songs he’s already put down. “I loved the sound, so I re-recorded some of the earlier stuff that I’d done because I was playing it better,” Emmanuel says. “There was more bounce, and there was more joy in the music.” So it is that Emmanuel is moving cheerily forward, trusting that the optimism in his work will provide the same inspiration for the audience that the process provides for him. The frenzy in “The Bug,” the upbeat buzz of “Hope Street” and the serenity that blankets “Miyazaki’s Dream” all link into some form of positivity and possibility. It inspires Emmanuel, and it’s his hope that the indefinable spirit in those songs in turn inspires the audience. “I know why I’m here,” he says. “I know it’s not brain surgery, I know I’m not saving someone’s life. I’m just a musician trying to do his best, but each one of us has to do that, and that’s what makes the whole thing work.” Emmanuel embraced his individuality when he set out on his own as a musician. It required a change in his thinking and a belief in his unique destiny. Accepting that change at every stage of life is the point behind It’s Never Too Late. And that includes accepting the imperfections – the finger noise – along with the obvious accomplishments. “We are all creatures of habit, and 99% of people play the same tapes over and over in their subconscious,” Emmanuel says. “We see things that way because that’s who we are, it’s coming through our filter, so let’s change the filter. It’s never too late to make your life better.”